Eindhoven

University of Technology

Department of

Applied Physics

Group

Elementary Processes in Gas Discharge

N-Laag, G2.04,

5600MB Eindhoven

e-mail:

mfgendre@tue.nl

web site:

http://www.geocities.com/mfgendre

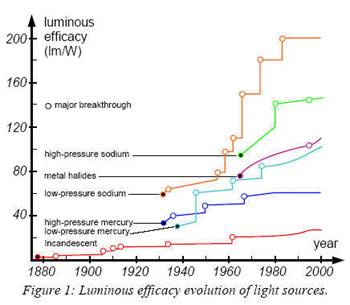

Light,

and ways of producing it, undoubtedly belongs to the most fascinating and

exciting kind of science man has ever tried to master. To be more exact,

light sources do not belong to one kind of science but embody most of them.

This is the development of vacuum techniques, of particular glasses, the

purification of gases, the refinement of metals, the elaboration of

fluorescent substances, and other countless engineering feats that allowed

the making and improvement of all lamps we depend on today.

Of

course, many of these breakthroughs were precisely driven by the need for

better light sources, having longer lifetimes, higher efficiency and

better color properties. Yet, no one suspects that two centuries of

scientific research, discoveries, developments and refinements stare upon

us every time we flip a switch to give birth to light.

It was

exactly two hundred and one year ago that Humphry Davy set the foundations

of the lighting industry with his simultaneous discoveries of light

emission from incandescent metal wires and from electrical arcs (also by

W. Petrov). Until 1802, and since 400,000 BC, man had relied solely on

fire for his lighting needs.

The

invention of the electric pile by Alessandro Volta in 1800 opened a brand

new era of perspectives. His stacks of copper, zinc and saltwater-soaked

cardboards allowed the circulation of steady flows of electric currents

that would eventually spark the lighting revolution. A revolution that was

indeed slow to start.

The

early years

The

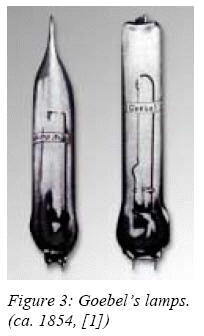

discoveries of Davy and Petrov had to wait five decades, the development

of steam-powered dynamos and the refinement of Volta’s battery, before

becoming a practical reality. By 1850, Léon Foucault built the first

carbon arc lamp that was subsequently used for theatrical lighting, while

four years later Einrich Goebel, a German emigrant in the USA, made the

first practical incandescent lamps. His sources were made of carbonized

bamboo filaments enclosed in evacuated perfume bottles, and were intended

to illuminate the shop window of his watch shop in New York city.

A third

way of electric lighting emerged in 1856 from the discovery by Michael

Faraday (England) of the electric glow discharge in rarefied gasses

(1831-35). This year, Julius Plücker and glass blower Enrich Geissler

started some systematic investigations of electrical discharges in

evacuated glass tubes provided with electrodes at each end. Subsequent

experiments from Hittorf, Crookes and Golstein revealed that the light

color of the discharge changed upon the addition of other gases and vapors.

This phenomenon was finally understood in 1859, when Robert Bunsen and

Gustav Kirchoff showed that each chemical element emits a specific set of

light colors, or spectral lines. This discovery eventually set the

foundations of spectroscopy. However, the inner working principles of

these tubes were not understood until the 1920s, when General Electric

(GE, USA) scientist Irving Langmuir studied and made the first accounts of

the physics of ionized gases, and coined the term plasma to

describe them. Then for this reason and others, “Geissler” and “Crookes”

tubes were relegated to the rank of lab curiosities until the beginning of

the twentieth century.

On the

side of carbon arcs, many improvements followed the lamp of Foucault. From

the work of Foucault and Dubosc, Serrin designed in 1859 a mechanical

system to keep the arc at a given position despite the unequal burning

rate of the cathode and the anode. Later, Crompton in England and

Wallace-Farmer in the USA made an arc lamp that was regulated in voltage,

thus permitting its use in series circuits. A further major step followed

in 1870, when Russian engineer Paul Jablochoff invented a self-regulating

arc lamp made of two close graphite rods separated by a layer of plaster

of Paris. These lamps had a lifetime of 90 minutes, and a set of

electrodes could not be re-ignited once it has been used. Despite its many

drawbacks, this kind of source led in 1878 to the first practical electric

arc street lighting in Paris. Two years later, Compton and Pochin in

England and Friedrich von Hefner-Alteneck in Germany invented the

differential carbon arc lamp, which was power-regulated by monitoring both

arc current and voltage. This system eventually superseded Jablochoff’s

lamp in street and industrial lighting.

Carbon

arc systems were pretty crude, cumbersome, noisy, dirty and drew a lot of

electrical power.

Beside

this, its bright harsh light did not make it suitable for home lighting.

The consequence is that many persons looked for a better and softer way of

producing light, and it was already of common knowledge that a piece of

carbon or metal heated by a current would do the job. However, things

sound far simpler than they are, and most of the attempts went up in smoke

as all materials eventually caught fire. The culprit was not so much the

filament material than the poor quality of vacuum in early lamp

prototypes.

Emergence

and development of practical incandescent lamps

The

development of incandescent filament lamps owes a lot to that of vacuum

pumps.

In 1838 it was discovered that carbon brought to incandescent does not

consume in a air-free environment. From this knowledge the enclosed arc

lamp was born in 1893 (Jandus and Mark) and had a lifetime of 150 hours,

or three to five times that of lamps burning in free air. Although it was

known that platinum wires could be brought to incandescence in open air

for a long time (de la Rue, 1802), the need for lamps with higher filament

temperatures was felt. Carbon rods were studied and used by J.W. Starr and

M.J. Roberts between 1840 and 1854. The former made in 1845 a lamp

partially evacuated with a mercury column from Torricelli’s barometer.

Lodyguine, a Russian scientist, circumvented in 1856 the problem of poor

vacuum by using an atmosphere of nitrogen instead. Two hundred of his

carbon rod lamps were successfully used for lighting the harbor of St

Petersburg. These first lamps, although successful in their own right, did

not show a good lifetime due to the presence of residual impurity gases

either in nitrogen or in vacuum. Two major breakthroughs speeded up the

development toward a commercially viable lamp. First, in 1865 Sprengel

invented the mercury-drop vacuum pump, which was much better than von

Guericke’s pump developed around two hundred years before. This new device

could evacuate a vessel down to at least a ten thousandth of the

atmospheric pressure (10 Pa), a factor hundred lower that previously

achieved. L. Boem then improved this pump in 1878, and reached a millionth

of atmospheric pressure (10 mPa).

However, no matter how good lamps were pumped down, their lifetime was

still too short (several hours at best). The reason for this was

discovered in 1879 by Francis Jehl and Thomas Edison (USA), who found that

gases occluded in lamp materials are released in vacuum over time. They

then patented an effective outgassing method, which consisted of heating

the lamp during the pump-down process. In February of this same year,

Joseph Swan demonstrated a working incandescent graphite rod lamp before

the Royal Institution in Newcastle, England. This was eight months before

Edison made his successful low resistance carbon filament lamp.

Historically, Swan was the first to achieve a working carbon incandescent

lamp. However, the lamp lifetime was reportedly too short to be

commercially viable, which was not the case of Edison’s lamp. Edison

primarily used a U-shaped carbonized cotton thread for the filament, later

replaced by a carbonized bamboo fiber which boasted a luminous efficacy of

2 lm/W (ten times lower that today’s standard filament lamps) and a

lifetime of 45 hours.

By the

end of the 1870’s, the principles for making

a good incandescent lamp were established, and it was then agreed that a

low resistance filament was needed for its use in parallel circuits. This

set the requirements for thinner filament, which are prone to burn out

quickly in poor vacuum. A better lamp thus called for stringent

improvements of the making procedures and the quality of the materials.

Then from 1880 to 1883 many inventors worked at improving the quality of

the carbon filament. Swan came up with a novel process that consisted of

squirting reconstituted cotton into threads, which were carbonized into

very fine carbon filaments of constant diameters. In 1894, A. Malignani

introduced the use of red phosphorus as a chemical getter, which maintains

an excellent level of vacuum in the bulb throughout the lamp life.

making

a good incandescent lamp were established, and it was then agreed that a

low resistance filament was needed for its use in parallel circuits. This

set the requirements for thinner filament, which are prone to burn out

quickly in poor vacuum. A better lamp thus called for stringent

improvements of the making procedures and the quality of the materials.

Then from 1880 to 1883 many inventors worked at improving the quality of

the carbon filament. Swan came up with a novel process that consisted of

squirting reconstituted cotton into threads, which were carbonized into

very fine carbon filaments of constant diameters. In 1894, A. Malignani

introduced the use of red phosphorus as a chemical getter, which maintains

an excellent level of vacuum in the bulb throughout the lamp life.

The

search for higher luminous efficacies and color temperatures pushed the

research toward higher filament temperature. Besides a shortening of their

lifetime, this led to the severe blackening of lamp bulbs as carbon has a

high vapor pressure. Then, more refractory filament materials were needed

in order to reach more than 1200ºC. In 1893, Lodyguine investigated

several metals, which included tungsten, while four years later Carl Auer

von Welsbach succeeded at making an osmium filament lamp that was put on

market in 1902. Followed in 1905, Dr Hans Kuzel made the first

(brittle) tungsten filaments, which were used in new lamps marketed the

year after. This novel source pushed the lifetime up to 1000 hours and had

an efficacy of 8 lm/W (two times that of carbon filament lamps), which

eventually put an end to the osmium lamp of Auer von Welsbach. In 1907,

these lamps were also made to operate on 110V mains and were available up

to the 500W size. The next major breakthroughs happened from the work of

William Coolidge (General Electric, USA), who in 1910 succeeded at making

ductile tungsten filaments (as opposed to those made until then). Because

of its higher mechanical strength, this filament could be operated at a

higher temperature, thus boosting the lamp efficacy to 10 lm/W. Two years

later, Langmuir discovered the benefits of coiled tungsten filaments

operating in inert atmospheres (nitrogen, then argon-nitrogen mixture).

The winding permitted a reduction of the filament thermal losses, while

the surrounding gas lowered its evaporation rate. Both combined, this gave

a lamp efficacy of 12 lm/W (first marketed by GE in 1913 in 500, 700 and

1000W sizes) and spelled

first

(brittle) tungsten filaments, which were used in new lamps marketed the

year after. This novel source pushed the lifetime up to 1000 hours and had

an efficacy of 8 lm/W (two times that of carbon filament lamps), which

eventually put an end to the osmium lamp of Auer von Welsbach. In 1907,

these lamps were also made to operate on 110V mains and were available up

to the 500W size. The next major breakthroughs happened from the work of

William Coolidge (General Electric, USA), who in 1910 succeeded at making

ductile tungsten filaments (as opposed to those made until then). Because

of its higher mechanical strength, this filament could be operated at a

higher temperature, thus boosting the lamp efficacy to 10 lm/W. Two years

later, Langmuir discovered the benefits of coiled tungsten filaments

operating in inert atmospheres (nitrogen, then argon-nitrogen mixture).

The winding permitted a reduction of the filament thermal losses, while

the surrounding gas lowered its evaporation rate. Both combined, this gave

a lamp efficacy of 12 lm/W (first marketed by GE in 1913 in 500, 700 and

1000W sizes) and spelled

the end

of all carbon and other straight filament lamps.

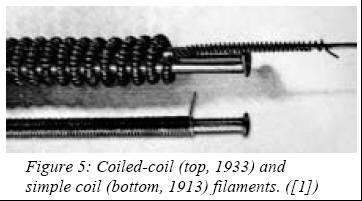

From

this point on, the development of incandescent sources slowed down. In

1933, the first coiled-coil tungsten filament lamp was made available for

general lighting, although it was already in use since 1913 for projection

purposes. The following years saw the introduction of krypton and

xenon-filled lamps having higher filament temperatures owing to reduced

evaporation rates. The impact of these later lamps was limited because the

use of heavier gases did no lead to an efficacy increase higher than ten

percents.

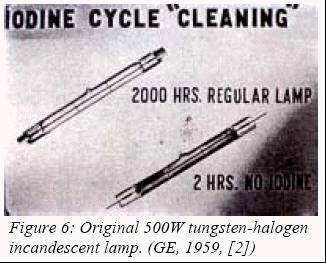

The

last major advance in this domain happened at the end of the 1950’s with

the making by Zuber and Mosby (GE) of the first viable tungsten lamp

having a filling of halogens. The presence of this class of elements

allows a chemical cycle to return evaporated tungsten atoms back to its

source. This permitted the use of ultra-compact packages with 100% lumen

maintenance throughout lamp life (no bulb blackening). Also, its efficacy

was raised to 20 lm/W

an

later to 26 lm/W, thus making the most efficient incandescent lamp yet.

These sources were first marketed in 1962 and triggered an explosive

development of compact lamps for general, studio, automotive, flood

lighting and movie projection. In the 1980’s the first low voltage capsule

lamps integrated or not in compact reflectors were put on the market,

while infrared-reflecting coatings were tried at the beginning of the

1990’s in an attempt to further decrease the thermal losses of the

filaments.

an

later to 26 lm/W, thus making the most efficient incandescent lamp yet.

These sources were first marketed in 1962 and triggered an explosive

development of compact lamps for general, studio, automotive, flood

lighting and movie projection. In the 1980’s the first low voltage capsule

lamps integrated or not in compact reflectors were put on the market,

while infrared-reflecting coatings were tried at the beginning of the

1990’s in an attempt to further decrease the thermal losses of the

filaments.

Their

pathetic efficacies make incandescent lamps more suitable for heating

purpose than lighting. However, low production costs and simplicity of use

(no current-limiting ballast required) ensures them several decades of

strong use at home and for commercial lighting. If the future see the

development of stable up-converting phosphors transforming infrared into

visible light, or that of proper tungsten optical band-gap crystals, then

incandescent sources will be able to compete with vapor discharge lamps.

The rise

of electric discharge and arc lighting

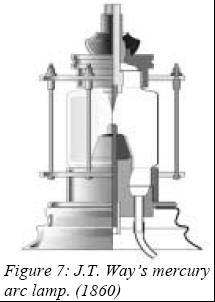

The

only practical light sources worked out until 1860 where of incandescent

nature. Even the brilliant carbon arc emits its light mainly from the

white-hot anode; the contribution from the arc being relatively

negligible. This year, on September 3

rd , the Hungerford

suspension bridge

in

London was lighted with the first mercury arc lamps ever made. This

invention from J.T. Way was a carbon arc enclosed in an atmosphere of air

and mercury vapor. This was the first time the arc itself was the source

of light. Mercury in light sources poses today an environmental threat and

work are carried out to suppress it. By then it made a lot of sense to use

it, as this is the only metal with an appreciable vapor pressure at room

temperature and can emit a large proportion of visible light when

energized in electrical discharges. This known fact led to the invention

of the low-pressure mercury lamp by Peter Cooper-Hewitt (USA) in 1901,

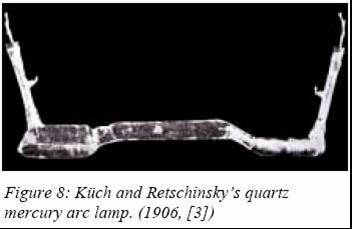

followed by a quartz atmospheric-pressure version by R. Küch and T.

Retschinsky (Germany) in 1906 (marketed in 1908 by Westinghouse).

in

London was lighted with the first mercury arc lamps ever made. This

invention from J.T. Way was a carbon arc enclosed in an atmosphere of air

and mercury vapor. This was the first time the arc itself was the source

of light. Mercury in light sources poses today an environmental threat and

work are carried out to suppress it. By then it made a lot of sense to use

it, as this is the only metal with an appreciable vapor pressure at room

temperature and can emit a large proportion of visible light when

energized in electrical discharges. This known fact led to the invention

of the low-pressure mercury lamp by Peter Cooper-Hewitt (USA) in 1901,

followed by a quartz atmospheric-pressure version by R. Küch and T.

Retschinsky (Germany) in 1906 (marketed in 1908 by Westinghouse).

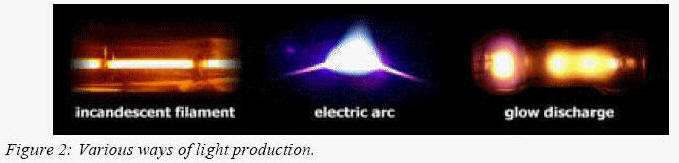

These

lamps performed stunningly well by 1900 standards, they had efficiencies

many times that of carbon filament lamps. The reason for this resides in

the light emission mechanisms that are different in these two kinds of

lamps. Incandescence arises from high thermal energy (i.e. lattice

vibrations in the filament material) that allows the emission of visible

light. Consequently, a large portion of the emitted radiation is in the

infrared (95% of input energy in standard filament lamps). As opposed to

this, an electric discharges and arcs emit their light upon excitation and

relaxation of gas or vapor atoms and molecules from electron impacts. Thus

more input energy can be radiated into useful visible light, leading to

much higher efficiencies (e.g. 35% visible light for low-pressure sodium

vapor). However, the difference between the two kinds of light sources

lies also in their emission spectra. If incandescent lamps give excellent

light color renditions, electric discharge lamps at this time did not.

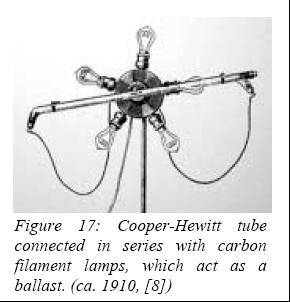

It was

recognized that Cooper-Hewitt and Küch- Retschinsky lamps emitted a bluish

light deficient in red, thus having poor color rendering properties. This

limited their use to streets, warehouses and industries. This particular

problem was addressed with series connected filament lamps that provided

the additional red light and stabilized the electrical discharge.

The

extensive use of both types of mercury lamps started when proper

electrodes were developed. Until the 1930’s, the original lamps had

electrodes made of mercury pools, which waste a lot of electrical energy

for the supply of electrons to the discharge.

High-pressure mercury lamps – the forerunners

The

lamp from Küch and Retschinsky had a limited success due to many unsolved

problems, like proper electrodes, no tight quartz-to-metal seals and

strong UV emissions leading to skin injuries. In the beginning of the

1930’s, many lighting companies worked to address these problems and aimed

at presenting an atmospheric-pressure mercury lamp on the market.

In

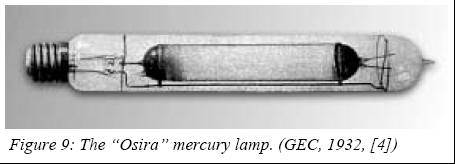

1932, General Electric Company of England (GEC) was the first to present

such a lamp under the trade name “Osira”.

In

1932, General Electric Company of England (GEC) was the first to present

such a lamp under the trade name “Osira”.

Because

no satisfactory sealing technique between quartz and tungsten was found,

this lamp used a discharge tube made of aluminosilicate hard glass. The

relatively low softening temperature of this material limited the power

loading of the electric arc to 10-100 W/cm and restricted its use to the

vertical position. This

later

problem was eventually solved by the use of an electromagnet that kept the

arc straight when the lamp was horizontally operated.

later

problem was eventually solved by the use of an electromagnet that kept the

arc straight when the lamp was horizontally operated.

The

efficacy of such lamp was 30 to 40 lm/W, with a lifetime of a couple of

thousands hours. The low power loading of the arc and the subsequent

electrode power losses did not allow the making of efficient low-power

mercury lamps. Only the 400 and 250W sizes were made available in this

configuration. Also worth of interest, these original lamps did not

integrate any starting aid, like an auxiliary probe. Thus GEC fitted each

luminary with a small Tesla coil in order to ignite the lamp. This was

certainly the first time that an igniter was used.

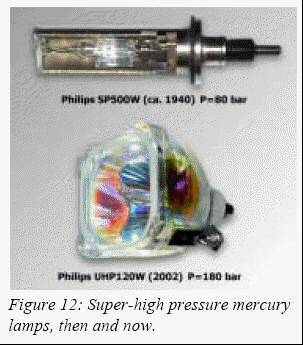

By the

end of the 1930’s, Willem Elenbaas (Philips, the Netherlands)

theoretically predicted a rise of mercury lamp efficacy with the increase

of the arc power loading. This was effectively verified after the

invention of quartz-to-tungsten graded seals in 1935 (20 atmosphere) lamp,

the HP300 (75W). This was followed by a breakthrough source: the

water-cooled SP500W working at 80 atmospheres (Philips). Not only these

lamps had a better efficacy (40 and 60 lm/W respectively), they also

showed improved color rendering properties owing to the higher operating

pressure.

The

SP500W lamp was primarily designed and used for film projection and

floodlighting applications, while the HP300 remained favored for street

and industrial lighting due to its still insufficient emission of red

light. This problem of color rendering pushed the research toward color

improved lamps that used an integrated incandescent filament (acting also

as a ballast - 1941) and/or a phosphor coating on the inner surface of the

outer bulb to transform useless ultra violets into red light, thus filling

the gap in the mercury spectrum.

In

1934, cadmium sulfide was found to be a suitable fluorescent material,

although it provided only a mild color correction. The introduction of the

color-corrected mercury lamp was made possible with the elaboration of

manganese activated magnesium germanate and fluorogermanate in 1950, which

improved greatly the color rendering index and had a beneficial effect of

the lamp efficacy. Three years later, tin-activated orthophosphate was

introduced, and in an attempt to have proportionally more red emission,

“deluxe” lamps with a rosy glaze on the outer bulb were marketed for a

short while by a number of manufacturers (1956).

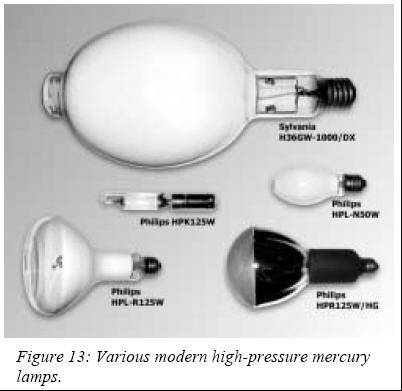

Then in

1967, the hugely successful europium-activated vanadate and

phospho-vanadate phosphors inherited from color TV technology were

introduced and are still in use today. These modern color improved mercury

lamps have a color rendering index (CRI) of 65 against 15 for clear lamps

and a luminous efficacy of 60 lm/W.

The

present design results from a large number of improvements in the lamp

structure that occurred in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Among

them are new kinds of quartz-to-metal seals using 20 micron-thick

molybdenum foils pressed in quartz. Also, the changeover from thorium to

alkali oxide electrodes (Osram, Germany) permitted a better lumen

maintenance throughout lamp life.

The

last major innovation concerning these lamps occurred in 1998 with the

invention of UHP (Ultra High Performance/Pressure) lamps by Hanns Fischer

(Philips) for LCD projection purposes. These new sources operate with an

internal pressure of about 200 atmospheres, thus leading to a strong

continuum in the emission spectrum and a high arc power loading. These

make this kind of lamp efficient (60 lm/W) and optically small (0.7 mm arc

gap), thus allowing for an excellent optical control.

Standard high-pressure mercury lamps (not UHP) are today on the brink of

extinction because of the environmental threat posed by mercury, and their

relatively poor performances compared to metal halide and high-pressure

sodium sources.

Metal

halide lamps – the legacy of mercury sources

It was

recognized since the earliest days of mercury lamps that the lack of red

light in their emission spectrum impeded heavily on their widespread use.

In 1906, Guercke already suggested to add some red emitting metals to the

lamp of Küch and Retschinsky in order to improve its color properties. M.

Wolke followed this procedure in 1912 and used cadmium and zinc. This

turned out to be unsuccessful due to a low lamp cold-spot temperature

(600ºC), which led to an insufficient zinc and cadmium vapor pressures.

Also, these metals readily attacked the quartz envelope, thus rendering

the lamp useless after a couple of tens of hours of operation.

The

development of suitable fluorescent materials and ballasting filaments

dampened the need for color improved mercury arcs. However, studies were

still going on possible additives for the mercury lamp in order to

increase its luminous efficacy, regardless of color properties. In 1941,

Schnetzler made a mercury-thallium lamp having an efficiency of 70 lm/W,

almost twice as high as its mercury counterpart. The desired thallium

vapor pressure was reached by operating the arc tube at thrice its normal

power

The

development of suitable fluorescent materials and ballasting filaments

dampened the need for color improved mercury arcs. However, studies were

still going on possible additives for the mercury lamp in order to

increase its luminous efficacy, regardless of color properties. In 1941,

Schnetzler made a mercury-thallium lamp having an efficiency of 70 lm/W,

almost twice as high as its mercury counterpart. The desired thallium

vapor pressure was reached by operating the arc tube at thrice its normal

power

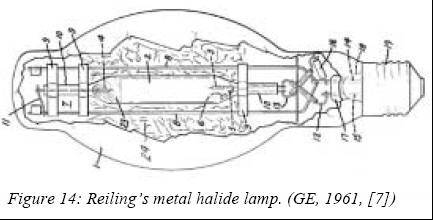

loading, with the consequence we can imagine on the life expectancy. In

the next decade, studies turned toward metal-halogen compounds that have

higher vapor pressures than metals at a given temperature. Gilbert Reiling

(GE) patented the first metal halide lamp in 1961, which was intended to

replace high-pressure mercury lamps in their sockets. It had a filling

primarily of mercury, thallium and sodium iodide that showed a sizeable

increase of lamp efficacy (up to 100 lm/W) and color properties, and made

it more suitable for commercial, street and industrial lighting.

Eventually GE marketed this lamp in 1964 with additives of sodium and

scandium iodides instead.

Most

major manufacturers followed shortly thereafter, with varied compositions

in order to meet different lighting needs and to circumvent competitors’

patents. Today the most popular additives are sodium-scandium iodides,

lithium soitum-thallium-indium halides and several mixtures of rare-earth

halides.

The

sixties and seventies witnessed a furious development of metal-halide

lamps in different geometries from tubular to reflector, and in power

range between 175W and 5000W in order to meet the soaring demands in the

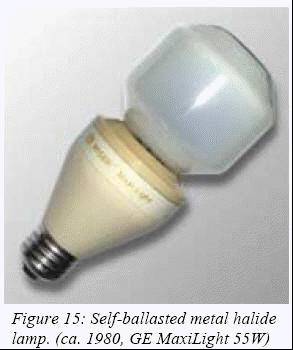

many applications it found. One of the last strongholds this kind of

source did not invade was at home. At the end of the 1970’s GE, Sylvania

(USA) and Philips designed prototypes of self-ballasted metal-halide lamps

intended to replace standard filament lamps for domestic applications.

This was ultimately proven unsuccessful due to some lethal drawbacks such

as the lack of hot re-strike capabilities and the prohibitive cost of the

lamps.

Two

major breakthroughs followed at the beginning of the 1980’s. In 1981,

Thorn Lighting (England) presented the first metal halide lamp with a

sintered alumina ceramic discharge tube, which resulted from ten years of

research and development. Unfortunately, this revolutionary source did not

reach the market due to a lamp voltage/current characteristic that did

not match any available ballast. Around the same year, and with more

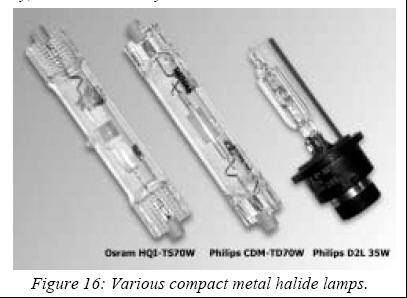

success, Osram introduced its compact double-ended HQI-TS lamps that found

an application in shop-window and commercial lighting.

did

not match any available ballast. Around the same year, and with more

success, Osram introduced its compact double-ended HQI-TS lamps that found

an application in shop-window and commercial lighting.

In

1991, Osram, Philips, Valeo and many other car equipment manufacturers

engaged themselves in the ‘vedilis’ project, which led to the

xenonmetal halide lamps (D1 and D2) for automotive headlights. Philips

then revived metal halide lamps with ceramic discharge tubes in 1995, when

it launched its range of CDM lamps. Osram and GE soon followed. These

lamps present today an alternative to high-pressure sodium sources for

downtown street lighting. The use of this particular design allows for a

better lamp-to-lamp color matching, higher efficacies and better color

rendering. Even more so, the bluish light of metal halide performs better

than the orange hue of high-pressure sodium when scotopic vision prevails

in low illumination levels at night.

Low-pressure mercury

fluorescent lamps – toward domestic applications

The

origin of fluorescent tubes goes back to the invention in 1901 of the

low-pressure mercury lamp by Cooper-Hewitt. For the same reasons as its

high-pressure counterpart, its use was restricted to places where color

rendering was not an issue. Right from the start, Cooper-Hewitt worked to

improve his lamp by applying some fluorescent dyes (primarily Rhodamine B)

on the bulb surface and later on luminary reflectors in order to

compensate for the lack of red emission. The idea of using fluorescence to

convert invisible light into useful radiation was not new, and already in  1859

E. Becquerel tried to use Geissler tubes filled with fluorescent materials

in order to get a practical light source. His trials were not successful

as the efficacy was too low. Later in 1896, one year after the discovery

of X-rays by W. Röntgen, T. Edison made a X-ray lamp internally coated

with calcium tungstate which radiated a bluish white light. This source

was three times as efficient as carbon filament lamps, and had X-rays not

caused severe injuries, this lamp would have certainly been the first

commercial fluorescent source.

1859

E. Becquerel tried to use Geissler tubes filled with fluorescent materials

in order to get a practical light source. His trials were not successful

as the efficacy was too low. Later in 1896, one year after the discovery

of X-rays by W. Röntgen, T. Edison made a X-ray lamp internally coated

with calcium tungstate which radiated a bluish white light. This source

was three times as efficient as carbon filament lamps, and had X-rays not

caused severe injuries, this lamp would have certainly been the first

commercial fluorescent source.

Back to

the twentieth century, it was discovered in 1920 that an electrical

discharge in a proper mixture of argon and mercury at low pressure could

radiate efficiently (60% of power input) ultraviolet light at 253.7nm and

184.9 nm. Six years later, Meyer, Spanner and Germer from Osram (Germany)

published a landmark report where they described a low-pressure mercury

vapor lamp provided with externally-heated oxide-coated electrodes, and an

internally phosphor-coated bulb to convert UV radiation into visible

light. This document set what would become the first successful

fluorescent tubes.

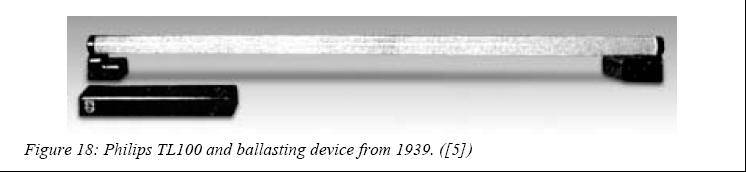

However, its marketing had to wait for the development of efficient

electron-emitting electrodes by M. Pirani and A. Rüttenauer (Osram) in

1932, and the elaboration of the calcium tungstate - zinc silicate

phosphor. Then in September of 1935, the first tubular fluorescent lamp

was demonstrated before the Illuminating Engineering Society in

Cincinnati, North America. This was presumably from General Electric, who

had taken over the patent of André Claude on a similar fluorescent tube in

1932. Osram followed in 1936, and displayed its ‘L’ lamp at the World

Exhibition held in Paris. Between 1936 and 1938, most major lamp

manufacturers made fluorescent tubes available both in Europe and in the

US for general lighting applications. These lamps had a tube diameter of

38mm, an efficiency of about 30 lm/W and a moderate color-rendering index,

yet good enough for its use at home.

In

1942, A.H. McKeag from GEC (England) made a giant leap with the discovery

of calcium and strontium-activated halophosphates. Lamps using this

phosphor formulation

were introduced in 1946 and had twice the efficacy of former tubes, while

the color rendering was much improved.

formulation

were introduced in 1946 and had twice the efficacy of former tubes, while

the color rendering was much improved.

Philips

made the next step with the introduction in 1973 of the three-band

phosphors. This boosted the efficacy up to 90 lm/W with excellent color

rendition (IRC 80-90). This new formulation also allowed the increase of

the lamp wall power loading and led to the reduction of the tube diameter

from 38mm (T12) to 26mm (T8), and then to 16mm (T5) at the beginning of

the 1980s.

A

decade later, Osram shrunk things further and put a 7mmdiameter (T2)

fluorescent tube on the market (Lumilux-FM).

The

reduction of lamp size permitted the design of compact fluorescent lamps

with integrated ballast. The first of this kind was presented by Philips

at a world technical conference held in Eindhoven in 1976. In 1980, this

company introduced successfully its SL*18, followed by an electronic

version in 1982. Competitors were quick to catch up and by the end of the

1980’s compact fluorescent lamps were widely available at a reduced cost

and package size. The success of these lamps was partly due to the energy

crisis that raised the cost of electric

consumption,

thus calling for more efficient and cost-effective light sources.

consumption,

thus calling for more efficient and cost-effective light sources.

At last

and not least, from the eighties until the mid-nineties several lamp

makers introduced electrodeless versions of fluorescent lamps. In these

sources the discharge originates from an electromagnetic field generated

by an induction coil antenna. The suppression of the electrodes increases

the lamp lifetime up to sixty to a hundred thousands of hours.

Fluorescent lamps were the first and only discharge lamps to reach the

level of domestic lighting. Today, they provide a wide range of color

temperature with excellent color rendition and high efficacies.

This

explains why they account for seventy percent of all lamps used in

commercial illuminations. Development still continues today, and

priorities are set to size and efficiency. To this respect, the use of

surface-mounted electronic components permitted the making of smaller CFL

lamps to fit in low-power luminaries, therefore claiming more ground to

its incandescent counterpart.

Low-pressure sodium lamps – reaching summits in efficacy

Extensive experiments with electrical discharges in alkali vapors could

have started only in 1920 when A.H. Compton formulated a borate glass

resistant to sodium. Alkalis, being strong reducers, require special

glasses as normal materials like soda-lime silicates are readily attacked

and lead to the formation of a brown light-absorbing film. Two years

later, in 1922, M. Pirani and E. Lax from Osram experimented sodium

discharges for lighting applications. The following year, Compton and C.C.

van Voorhis in the USA attained an efficacy of 340 lm/W with a lamp

externally heated by an oven. Naturally, the calculation of the efficacy

did not take into account the energy provided to keep the lamp at its

optimum working temperature of 260°C.

Then,

in 1931, both Philips and Osram made the first viable

low-pressure

sodium lamps, and the following year a stretch of road between Beek and

Geleen, in the Netherlands was lighted with Philips lamps. These sources

were DC-operated via an externally heated cathode and had an efficacy of

about 50 lm/W. A Dewar flask surrounded the discharge tube in order to

limit the thermal losses. In 1933 followed the AC-driven positive column

type of lamp, which had a higher efficacy partly due to a more favorable

current density in the discharge.

low-pressure

sodium lamps, and the following year a stretch of road between Beek and

Geleen, in the Netherlands was lighted with Philips lamps. These sources

were DC-operated via an externally heated cathode and had an efficacy of

about 50 lm/W. A Dewar flask surrounded the discharge tube in order to

limit the thermal losses. In 1933 followed the AC-driven positive column

type of lamp, which had a higher efficacy partly due to a more favorable

current density in the discharge.

From

1933 until 1958, lamps were composed of a separate discharge tube and a

double-walled vacuum flask. In 1958, Philips marketed an integral lamp,

which included the discharge tube within an evacuated bulb thus preventing

the former from getting dirty, as it was the case in the previous design.

Subsequent work was done on increasing the lamp efficacy by improving its

thermal insulation. A first solution consisted of enclosing the discharge

tube in several infrared-absorbing glass sleeves. Then infrared mirrors

made of gold or bismuth

thin

films were employed. Philips

made

a leap forward in 1965 with the introduction of the tin oxide

semiconductor mirror, and later the better tin-doped indium oxide film.

These materials exhibit a strong infrared reflectivity while being highly

transparent to sodium light.

made

a leap forward in 1965 with the introduction of the tin oxide

semiconductor mirror, and later the better tin-doped indium oxide film.

These materials exhibit a strong infrared reflectivity while being highly

transparent to sodium light.

This

led in 1983 to a lamp reaching the symbolic barrier of 200 lm/W (SOX-E, by

Philips), which is the highest efficacy reached yet.

The

reason why low-pressure sodium is so efficient at producing visible light

is that this element, under the right conditions, radiates an

almost-monochromatic yellow light almost coinciding with the peak

sensitivity of the human eye in photopic vision. Also, this yellow light

emission corresponds to transitions from the two lowest (resonant) energy

levels of sodium, thus allowing an efficient transfer of energy from the

electric discharge to the excitation of sodium atoms.

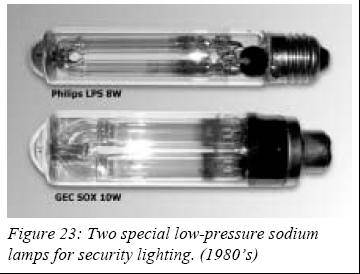

In the

1980s, several low-power lamps were experimented for replacing filament

lamps in security lighting. Technically these sources were successful but

their prohibitive cost and the need for specific ballasts prevented their

widespread use. Interestingly, Philips designed a LPS lamp that had

electrical characteristics closely matching that of existing fluorescent

tubes, so the ballasting equipment was already standard.

Today,

low-pressure sodium lamps remain unchallenged in terms of luminous

efficacy. Its bi-chromatic orange spectrum is the key to its efficiency,

but is also the limitation factor that restrains its use for street and

industrial lighting. In return, its light leads to excellent seeing

contrasts, particularly in foggy weather. Further developments of these

sources concern its high frequency operation and improvement of thermal

insulation, which will certainly bring the efficacy up to 230 lm/W in a

more or less distant future. Also worth of interest is the development of

electrodeless versions that obviate the need for life-limiting parts such

as the electrodes. These sources are however not likely to reach the

market due to difficulties in the making of a proper discharge vessel.

High-pressure sodium lamps – a compromise between color and efficacy

It was

known that increasing the pressure of a sodium discharge would lead to a

lower efficacy, but also to a broader and richer spectrum having better

color-rendering properties. The borate glass originally developed by

Compton and the other materials used in low-pressure sodium lamps are not

suitable for high-pressure operation. As the power loading and the

temperature of the discharge increase, the reactivity of sodium toward the

wall increases and lamps degrades

themselves within minutes of operation. Then, the development of the

high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamp had to wait for the work of Cahoon and

Christensen in 1955-57, and that in 1955 of R.L. Coble on tubes made of

sintered translucent alumina. This material was found to be resistant and

impermeable to alkalis, thus making it suitable for high-pressure sodium

lamps.

degrades

themselves within minutes of operation. Then, the development of the

high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamp had to wait for the work of Cahoon and

Christensen in 1955-57, and that in 1955 of R.L. Coble on tubes made of

sintered translucent alumina. This material was found to be resistant and

impermeable to alkalis, thus making it suitable for high-pressure sodium

lamps.

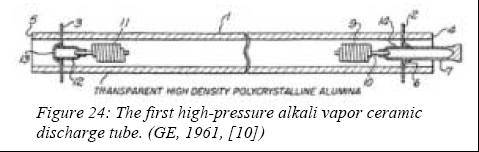

During

the following years, systematic studies were carried out on high-pressure

alkali discharges. Among them, cesium looked promising due to its

relatively white spectrum. However, the final choice was sodium because of

its good compromise between efficacy

and color rendering. The development of suitable sealing and manufacturing

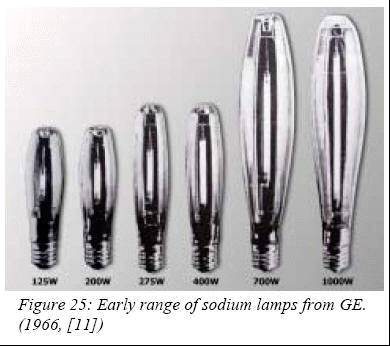

techniques allowed William Louden and Kurt Schmidt (GE) to make the first

practicable high-pressure sodium lamps in 1964. The next year, GE launched

an industrial full-scale production and a 400W lamp was made available in

1966 under the ‘Lucalox’ brand name. A 250W version followed three years

later. Their efficacies ranged between 90 and 100 lm/W with a life

expectancy of 6000 hours. Refinements in the 1980’s extended the lifetime

to 24,000 hours and the efficacy between 100 and 140 lm/W with a

color-rendering index of 20-25.

efficacy

and color rendering. The development of suitable sealing and manufacturing

techniques allowed William Louden and Kurt Schmidt (GE) to make the first

practicable high-pressure sodium lamps in 1964. The next year, GE launched

an industrial full-scale production and a 400W lamp was made available in

1966 under the ‘Lucalox’ brand name. A 250W version followed three years

later. Their efficacies ranged between 90 and 100 lm/W with a life

expectancy of 6000 hours. Refinements in the 1980’s extended the lifetime

to 24,000 hours and the efficacy between 100 and 140 lm/W with a

color-rendering index of 20-25.

The

design of this lamp was radically different than that of metal halide and

the mercury lamps. It also called for different types of ballasts. While

metal halide and mercury sources were and still are powered in the USA

with step-up leakage transformers, high-pressure sodium lamps required a

choke and an external igniter. Then followed several versions of lamps

with built-in internal switches that use the inductance of the choke to

kick-start the discharge tube.

Most of

these sources have a filling of mercury, xenon and sodium. The role of

xenon is to allow the lamp to start, while mercury sets the electric field

in the lamp discharge (positive column) and does not contribute to the

emission spectrum. Without it, the lamp voltage drop would be too low and

the current too high, thus requiring an inefficient and bulky ballast and

impairing the luminous efficacy. The environmental problems caused by

mercury forces its suppression, and mercury-free HPS lamps were made

available by mid 1990’s. These lamps have a higher xenon pressure and some

starting aid like sintered metal strips on the discharge tube surface

(Philips).

The

1980’s saw also the development of the so-called white HPS lamps by

Thorn, Philips and Iwasaki (Japan), which provide an incandescent-like

color at four times the efficacy of tungsten filament lamps.

These

sources are still popular today even with the advent of ceramic metal

halide lamps. The advantages of white HPS lies in the large portion of red

light in its emission spectrum, leading to a color temperature as low as

2500K. Metal halide lamps cannot reach such war white tone. Also worth of

notice is a lamp developed in the mid-1990s by Osram (DSX-T), which has

its color temperature that can be changed from 2700K (standard tungsten

white) to 2900K (tungsten halogen white) by a flick of a switch.

Bright

perspectives

The

field of lighting had many changes since the revolution in lifestyle and

lightstyle Davys’s discoveries induced! So affected has been and still is

the field of lamp manufacturing. The eighteenth century witnessed the slow

emergence of precursors that led to the exponential development of myriads

of sources in the next hundred years. By the dawn of the twentieth

century, thousands of lamp makers were struggling on a boiling market, and

to say the truth, it was not far from easy to jump in this business since

techniques and physics involved at this time were not as developed as

today. A century later, only three major (general) manufacturers have

survived: Philips, Osram and GE, who count more than 3500 references in

their product catalogs. A couple of hundred of medium-sized, minor or

specialized manufacturers surround them. They are now facing new

challenges that will change our lifestyle and lightstyle through the 21st

century: the development and extensive use of white LEDs, and the abandon

of harmful materials in all vapor discharge lamps while still pushing

upward their luminous efficacies and color rendering properties.

References

More

technical and historical details are available at:

http://www.geocities.com/mfgendre

[1]

F.J.M. Bothe, AEG-Telefunken Ontladingen/Schakels, 57 p., June

1979.

[2]

“Lighting progress in 1959”, Illuminating Engineering, pp.140,

March 1960.

[3] R.

Küch and T. Retschinsky, “Photometrische und spektralphotometrische

messungen am quecksilberbogen bei hohem dampfdruck”, Annalen der Physik,

vol. 20, pp. 563-583, June 1906.

[4]

C.C. Paterson, “Luminous discharge tube lighting”, The journal of good

lighting, pp.308-318, December 1932.

[5]

P.J. Oranje, Gasontladingslampen, Uitgave Meulenhoff & Co.,

Amsterdam, 288p., 1942.

[6]

J.L. Ouweltjes, W. Elenbaas and K.R. Labberté, “A new high-pressure

mercury lamp with fluorescent bulb”, Philips Technical Review, no.

5, pp. 109-144, November 1951.

[7]

G.H. Reiling, “Metallic halide discharge lamps”, US patent #3,234,421,

January 23rd, 1961.

[8] G.W. Stoer,

History of lights and lighting, Philips Lighting B.V., the Netherlands,

46 p., 1988.

[9] “Fifty years of

low-pressure sodium lighting”, Philips Lighting News, no. 8, 1982.

[10] K. Schmidt, “Metal

vapor lamps”, US patent #2,971,110, February 7th,

1961.

[11] W.C. Louden and

W.C. Matz, “High-intensity sodium lamp design data for various sizes”,

Illuminating

Engineering , pp.

560-561, September 1966.